Navigating the bureaucratic maze to obtain a passport is more than an administrative hurdle in Sudan; it’s a journey fraught with obstacles and uncertainty.

At 19, Mohammed Basheer was gearing up to complete his travel arrangements to Turkey to pursue his university education. However, with his passport’s validity less than four months, it wasn’t sufficient to obtain a visa. This situation meant he had to apply for a new one.

Well in advance of the academic year, Basheer made his application at the Nyala passport office, the capital of South Darfur State in western Sudan. But, the outbreak of war dramatically changed Mohammed’s life and that of his family, causing them to flee to El Fasher in North Darfur, nearly 195 kilometres away.

Once in El Fasher, he discovered that the local passport offices were closed. His only alternatives were to make the journey to Madani or Port Sudan. “The costs of travel and staying there are beyond what my family can manage,” says Mohammed, who remains undeterred in his quest for this essential document.

To compound his difficulties, even accessing the government’s electronic platform for passport applications proved challenging due to El Fasher’s inconsistent internet connectivity.

As the academic year looms, Mohammed’s chances of starting it on time are dwindling. This document hames his aspirations of becoming a software engineer, reflecting a broader issue.

Numerous students and patients face immense challenges leaving Sudan because of expired passports, barring them from attending overseas universities or seeking medical treatment abroad — especially critical as over 70 percent of health services in Sudan are disrupted by the war, as reported by the World Health Organization.

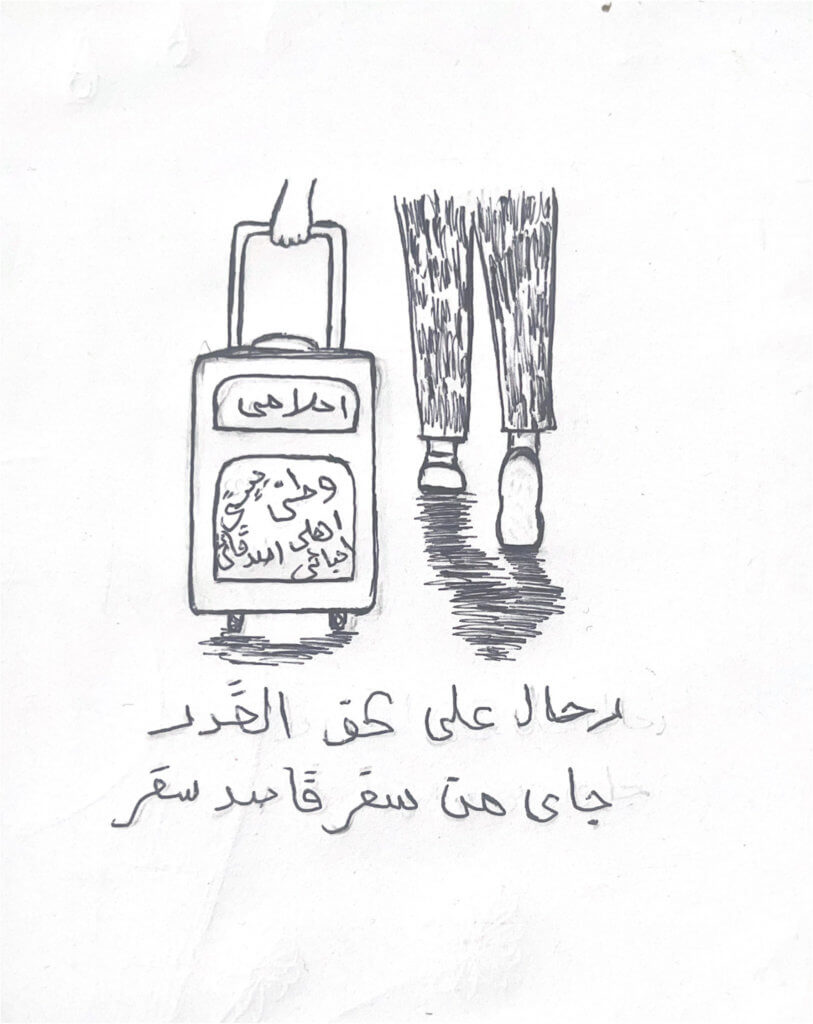

War-Torn Dispersal: Sudanese Families Fragmented by Conflict. (Illustration: Mazza Saleh)

Endless Suffering

Rania Abdel-Allah Adam, 33, narrates another ordeal. Her inability to get a passport means she’s separated from her family, now spread across Egypt, Libya, and Sudan. Moving from Nyala to El Fasher in August 2023 to get passports, they found themselves in limbo due to the shutdown of government services. “We’re stuck. We can’t progress to Libya nor have the funds to reach Port Sudan for passports. We’re saving whatever we can to reunite with my siblings in Libya.”

“We’re desperate to leave but are at a loss on how to proceed.”

Khadija Mohamadin, 40, shares a similar story. She lost all her official paperwork after fleeing the conflict in Zalingei city for El Fasher. “I had hopes of moving to Egypt to be with some relatives, but the lack of a passport halted me,” she says. And when passport applications were eventually announced, she discovered the Darfur cities were excluded, forcing her to consider travelling to Gezira State.

The challenges faced by Khadija and her family of five intensified. Besides travel costs, each passport now comes at a staggering 150,000 Sudanese pounds (roughly 250 US dollars) — a sum that seems insurmountable to her. “We’re desperate to leave but are at a loss on how to proceed.”

An Expensive Comeback

On August 30, 2023, there was a glimmer of hope when the Sudanese Ministry of Interior announced the resumption of passport issuance. But the new fee of 150,000 Sudanese pounds caused dismay, especially amongst those stranded, including patients, students, and expats.

This price increase caught many off-guard. Higher than the average global passport fee, it left many perplexed. The Ministry cited escalating paper and printing costs as justification. However, industry insiders noted that even top-quality electronic passports don’t cost more than 40 dollars each to produce, making this price hike seem excessive, especially given Sudan’s current economic hardships.

“Freedom of movement is a fundamental right.”

Human rights advocate Sharif Ali al-Sharif views these obstacles in obtaining passports as a clear breach of the right to freedom of movement. He references Sudan’s 2019 Constitution, which guarantees citizens the right to move freely, barring specific health and safety concerns, and the right to leave and re-enter the country. He states, “Freedom of movement is a fundamental right. Given Sudan’s present state, ensuring citizens can seek a better, safer life elsewhere is paramount.”

Al-Sharif urges the Sudanese government to uphold local and international laws, simplifying passport procurement and guaranteeing free movement for every citizen.

According to the Henley & Partners index, the Sudanese passport is 94th, allowing visa-free entry into 45 countries. However, for many in Sudan wishing to flee war, pursue education, or emigrate, acquiring this passport has become an elusive dream, compounded by the ongoing conflict and deteriorating national economic conditions.

______

This story was produced by Media in Cooperation and Transition (MiCT) and the North Africa Media Academy (NAMA), in collaboration with the Al Adwaa Media and Journalism Services Centre, and financed by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). The views expressed in this publication do not represent the opinions of MiCT, NAMA, Al Adwaa, or BMZ.