In a nation scarred by violent conflict, a deep dive into Sudan’s relentless pursuit of peace reveals the intricate dynamics of militarisation and the resilience of its people.

Few could have foreseen the severe deterioration of Sudan’s situation, one many now perceive as a point of no return. As one delves into Sudan’s current landscape, the tale weaves a complex tapestry of emotion, oscillating between despair and hope, bridging the past and present while gazing into the future.

It presents a multifaceted portrait of Sudan, leaving people to interpret its nuances. Yet, abruptly, the narrative shifts to a chilling revelation: war has erupted, rendering all the endeavours of the Sudanese to forestall it futile. It is April 14th, 2023, and what unfolds isn’t merely history; it’s a conflict fuelled by its provocateurs.

Amidst this backdrop, Abdulrahman Sharaf Al-Din, a human rights activist, aids emergency efforts established post-war to address the daily requirements of citizens, from medical to women-centric needs, especially in conflict zones. Having started with civilian resistance committees, Abdulrahman remains in Khartoum, navigating the war in his distinctive manner.

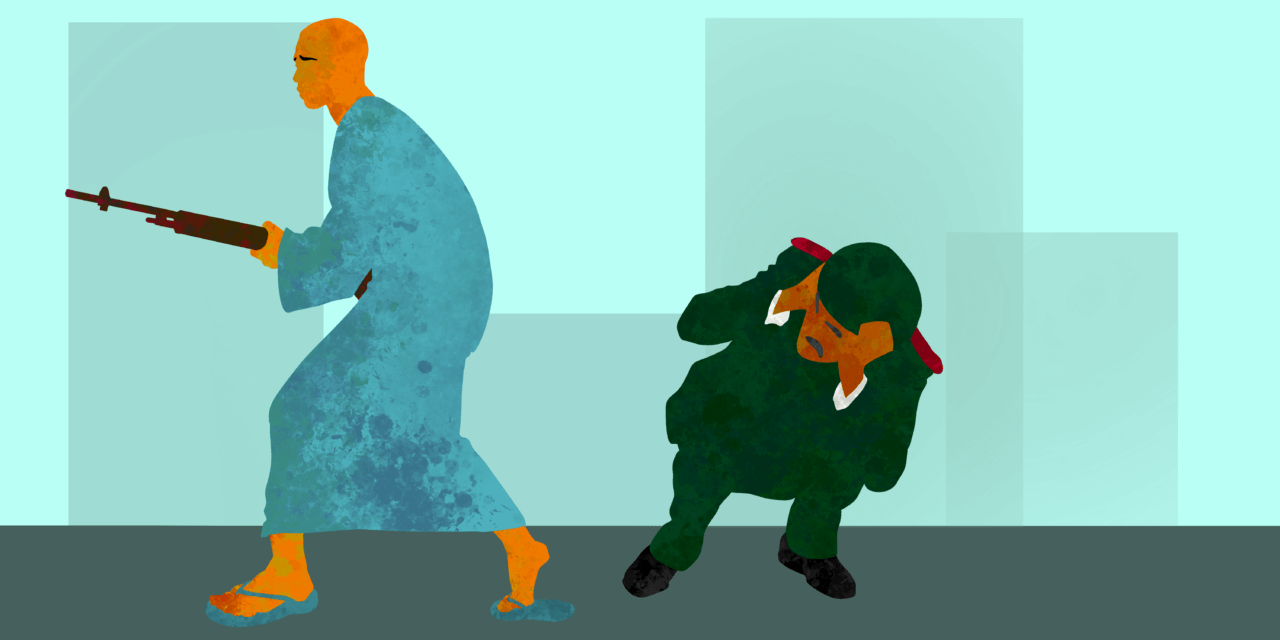

The onset of the war has accelerated the spread of weaponry via both popular and operational committee mobilisations, as well as individual acquisitions. This has heightened challenges for those residing in areas affected by conflict.

“We felt compelled to remain and make a difference.”

Prompted by these developments, Abdulrahman and his colleagues endeavoured to alleviate the chaos, focusing on the essential needs of the populace. He reflects, “After discussing potential outcomes with friends, we felt compelled to remain and make a difference. This led to the conception of the emergency rooms, although its implementation in our locale was delayed.”

Unexpectedly finding himself in Khartoum six months post-war, Abdulrahman hadn’t intended to stay long-term. He had returned from Atbara for a private endeavour when the conflict intervened. He candidly shares, “The reality is inescapable,” and paints a vivid picture of the ensuing mayhem: “Looting is rampant, homes are defiled. The mental toll is profound, and often, our efforts seem overwhelmingly insufficient.”

Yet, his resolve remains unshaken. Apart from his relief work, he chronicles wartime narratives, partakes in cultural events, organises initiatives for children, and even founded a public library. A notable achievement was the establishment of an emergency kitchen, “Ensuring meals for everyone, young and old, was a crucial step,” he recalls.

Sudan’s political landscape is rife with polarisation, and debates about mobilisation have become a daily discourse. Abdulrahman and his peers found themselves amidst this dialogue. However, they unanimously decided against taking up arms, stating, “It’s the duty of the military to safeguard us. They are financed by the state for this very purpose, not to render civilians as expendable.”

Abdulrahman’s stance against arming is rooted in his deep-seated beliefs. He fears a descent into civil discord where senseless violence prevails. He alludes to Al-Kalakla Al-Qubba, where despite arming the locals, the military failed to shield them, leading many to perilously flee across seas.

“Our efforts seem overwhelmingly insufficient.”

He is acutely aware of past misdeeds, where youth were conscripted and deceived under the guise of a noble cause, only to be exploited on the frontlines. Such experiences solidify his belief in the army’s exclusive role in defence, stating, “We face grave circumstances, but a scenario where all are pitted against each other is even graver.”

For Abdulrahman, his fervent wish remains for a sliver of hope, a chance for the Sudanese to reclaim their homeland, now marred by the cacophony of conflict. The increasing militarisation signifies a chapter bearing a price the Sudanese, including Abdulrahman, bear alone. He stands resolute, driven by a sense of national responsibility and profound love for his country.

______

This story was produced by Media in Cooperation and Transition (MiCT) and the North Africa Media Academy (NAMA), in collaboration with the Al Adwaa Media and Journalism Services Centre, and financed by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). The views expressed in this publication do not represent the opinions of MiCT, NAMA, Al Adwaa, or BMZ.