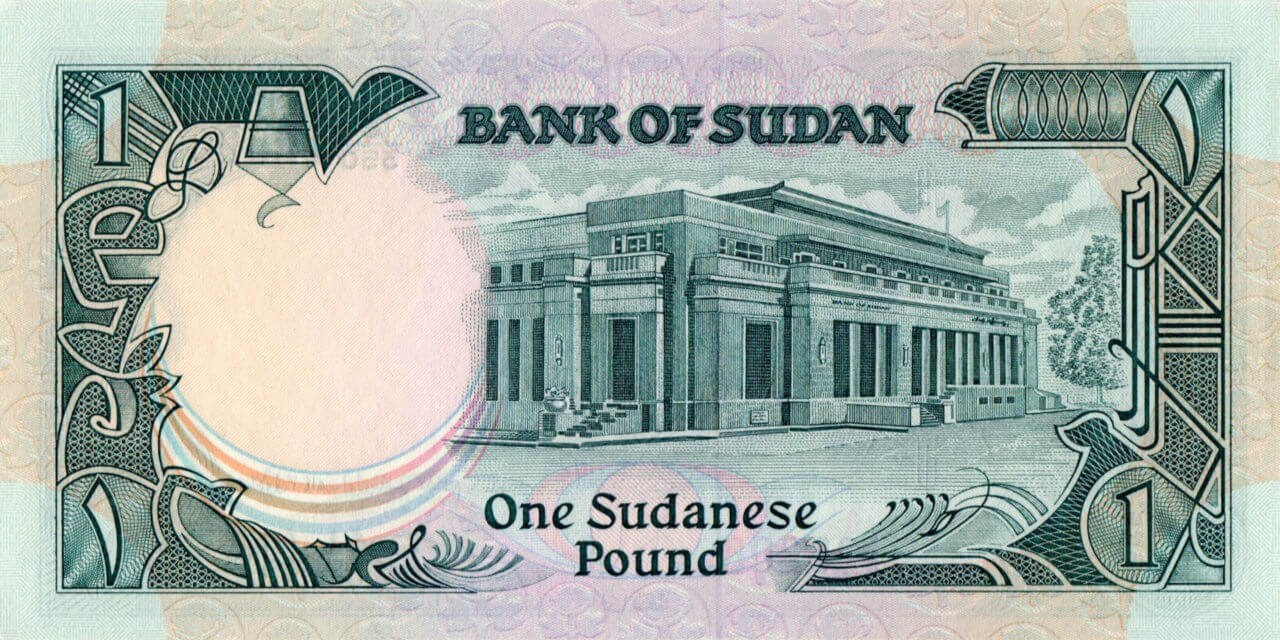

A one Sudanese Pound note (1987 series), featuring the headquarters of the Bank of Sudan. (cc) A. Heneen

The banking sector in Sudan is going through a confidence crisis as citizens are weary of unmet promises of better services, more accountability and transparency.

Ahmed Babiker, who works as an employee in the private sector in Sudan’s capital Khartoum, said that he used to spend hours in front of automated teller machines (ATMs) to withdraw even small amounts like SDG 2,000 (USD 40). “It was extremely difficult to get the amount I wanted when withdrawing money.”

Sudan has been short of hard currency for years. In November 2018, just weeks before nationwide protests, that eventually toppled the former regime of Omar a-Bashir, kicked off, many ATMs in Khartoum ran out of cash as the previous government scrambled to prevent economic collapse with a sharp devaluation and emergency austerity measures.

The demand for cash increased while Sudan’s central bank restricted the money supply to protect the Sudanese Pound. As inflation skyrocketed, trust in the country’s banking system vanished. “We as citizens have lost confidence in the banking system in Sudan,” said Ikram Abdelmajed, who also lives in Khartoum.

“It was extremely difficult to get the amount I wanted when withdrawing money.”

Ahmed Babiker

This factors combined contributed to a severe liquidity crunch, affecting citizens across the country, making their lives even more difficult. “There was a clear disturbance in transactions, and sometimes people were not able to withdraw their money because of the absence of liquidity.”

Sudan has suffered from a lack of foreign currency since losing three-quarters of its oil revenues when the south of the country seceded in 2011. The lifting of two decades of United States sanctions in October 2017 did not bring a hoped-for reprieve. Rampant inflation, strict withdrawal limits and mismanagement placed Sudan’s economy in deep trouble.

Sudanese Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok said in January that his country does not have foreign exchange reserves to protect the value of the Sudanese Pound, acknowledging the existence of a “structural defect”.

Inherited problems

In a TV interview broadcasted on January 21, Hamdok said that “the Bank of Sudan is one of the legacies of the former regime. It has turned into a commercial bank, speculating and trading in gold […]. We are working on developing a new law for the Bank of Sudan.” Beyond reforming Sudan’s central bank, the transitional government plans to improve the entire banking sector in the country.

Kamal Karrar, an economist and member of the Forces of Freedom and Change alliance (FFC) Economic Committee, told AlAdwaa.Online that “among the shortfalls of the banking system is the practice that credits go to persons without being recovered and this fact is being documented in reports and amounts of debt.”

This practice, in combination with other factors, has produced a liquidity crisis, according to Karrar. “Seventy-five percent of the cash is outside the banking system due to existing credit procedures, and this has created a confidence crisis between citizens and the banking system.”

“Stolen money should be recovered because it is public money.”

Kamal Karrar

Restoring the confidence of the Sudanese citizens in the banking system requires control and combating corruption, according to Karrar. He called for more effective measures and oversight of the banking institutions and the banking system.

“These remedies should be swiftly and urgently implemented,” Karrar said, adding that a first step should be “putting an end to the deep state and corrupt persons in the banking system”.

He stressed “the need to open the files of the banking system and hold those involved in corrupt practices accountable”. He also said that “stolen money should be recovered because it is public money.”

Flawed practices

According to Karrar, “the Islamic Murabaha system, adopted by the former regime, has deprived large segments of society of financial services, as banks required high guarantees.

Banking practices and policies in Sudan are problematic as they focus on short-term commercial financing. This kind of financing does not attract investments and is not beneficial to the economy because of its emphasis on trade and its negligence of other productive ventures.

“Among the complexities of the banking system is the fact that financing formulas only generate poverty and debt. This is because the conditions of loans are rigorous and require high guarantees,” said Karrar. “They do not allow ordinary people who want to start small businesses and need funds without high guarantees to benefit from them.”

Karrar emphasised the need to rethink banking and financial policies and to allocate more funds for productive projects, such as agriculture and industry. This, in turn, would mean that Sudan becomes more attractive for long-term investments.

“Financing formulas only generate poverty and debt.”

Kamal Karrar

“Specialised banks should get more support from the state, and the old roles of the Agricultural Bank and the Industrial and Real-Estate Bank should be restored to support the Sudanese economy. Moreover, the Islamic formulas should be reconsidered, and old traditional systems should be restored,” Karrer suggested.

Mohamed al-Nayer, an economics professor at the Al-Mughtaribeen University in Khartoum, suggested a “full restructuring” of Sudan’s banking sector. He suggested, “to support it with qualified employees, raise its financing capacities for developmental projects, increase the size of exports and decrease the trade balance deficit”.

In addition to restoring confidence in Sudan’s banking system within the country, international confidence-building is crucial to overcome the economic and banking crisis. A significant obstacle: Sudan is on the US list of state sponsors of terrorism.

A process with conditions

The US government added Sudan to its list of state sponsors of terrorism in 1993 over allegations that then-President Omar al-Bashir’s Islamist government was supporting terrorist groups. The US then imposed sanctions on Sudan in 1997, including a trade embargo and blocking government assets, for human rights violations and terrorism concerns. Washington layered on more sanctions in 2006 for what it said was complicity in the violence in Sudan’s Darfur region.

The US administration of President Donald Trump lifted these long-standing sanctions against Sudan In October 2017, saying it had made progress fighting terrorism and easing humanitarian distress. The move completed a process begun by former President Barack Obama, which removed a US trade embargo and other penalties that had effectively cut Sudan off from much of the global financial system. However, Sudan remained on the list of states that sponsor terrorism.

Al-Nayer said this constitutes a significant challenge for Sudan’s banks to operate successfully. “We can’t deal with all the banks in the world because Sudan is still on the list of states that sponsor terrorism. This makes foreign banks fear to deal with banks in Sudan so as not to be subject to sanctions and fines by the US administration.”

“We can’t deal with all the banks in the world.”

Mohamed al-Nayer

“Fraternal and friendly countries, such as Saudi Arabia, are in support of removing Sudan from the list. Perhaps there will be some difficulties, but it is a key step to resolve Sudan’s banking problem,” said al-Nayer.

In November 2019, a senior State Department official said that the US might remove Sudan from list of state sponsors of terrorism. However, Tibor Peter Nagy, the US Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs cautioned that doing so was a process with conditions.

“It’s not an event. It’s not flipping a light switch. It’s a process, and we are heavily, continuously engaged with our Sudanese interlocutors on how we can go about doing that,” he told reporters in a briefing according to Reuters.

“But the process required for delisting is widely misunderstood, the expectations for the results are exaggerated, and, most importantly, the real reforms necessary for economic recovery are grossly under-appreciated,” The Sentry’s Hilary Mossberg and John Prendergast argue.

They said “although delisting is an important for Sudan’s transition, it is just one of multiple steps needed – from both the US and Sudan – in order for pro-democracy forces to achieve their goals”, adding: “Sudan must prioritise reforming the banking sector to encourage private investment. Banking supervision remains weak, and the Central Bank’s capacity to crack down on corrupt banks is largely untested.”

The emergency programme

In September 2019, the Sudanese Finance Minister Ibrahim al-Badawi announced that the transitional government in Sudan would launch a 9-month economic rescue plan. Al-Badawi told reporters that “the emergency rescue plan would start in October [2019] and the most important pillar of it is the restructuring of the banking system”.

Among the steps taken already by the government is the drafting of a new law for the Central Bank of Sudan that preserves its independence. The barrier to the restructuring of the Central Bank is the inability of the Council of Ministers to interfere as it falls under the responsibilities of the Sovereign Council. Hamdok hopes to resolve this issue soon.

Al-Badawi warned against the liberalisation of the exchange rate as it might have a negative impact on the banking sector and he linked its liberalisation to a comprehensive reform of the banking sector. He said that “the exchange rate must not be exaggerated and exports and industry should be supported”.

“Now there are no liquidity problems at ATMs and the counters of the banks.”

Ahmed Babiker

Looking at the issue of liquidity, Sudan’s Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok said in a televised interview that the government emergency programme has succeeded in some aspects, among them is the liquidity. Ahmed Babiker confirms that the situation indeed has improved. “Now there are no liquidity problems at ATMs and the counters of the banks.”

This shows the first steps have been taken to navigate Sudan’s banking sector out of the confidence crisis. Hamdok’s government now has to enforce existing anti-money laundering laws and transparently implement banking supervision reforms, creating internal and external trust.

Karrar said that “if trust in the banking system is restored and if it recovers from its problems, it will produce an economic system capable of contributing to Sudan’s balance of trade and reduce the deficit. This way, foreign currencies will become available, and transactions will take place through the banking system.” Without it, the country probably will not see much in the way of economic improvement.